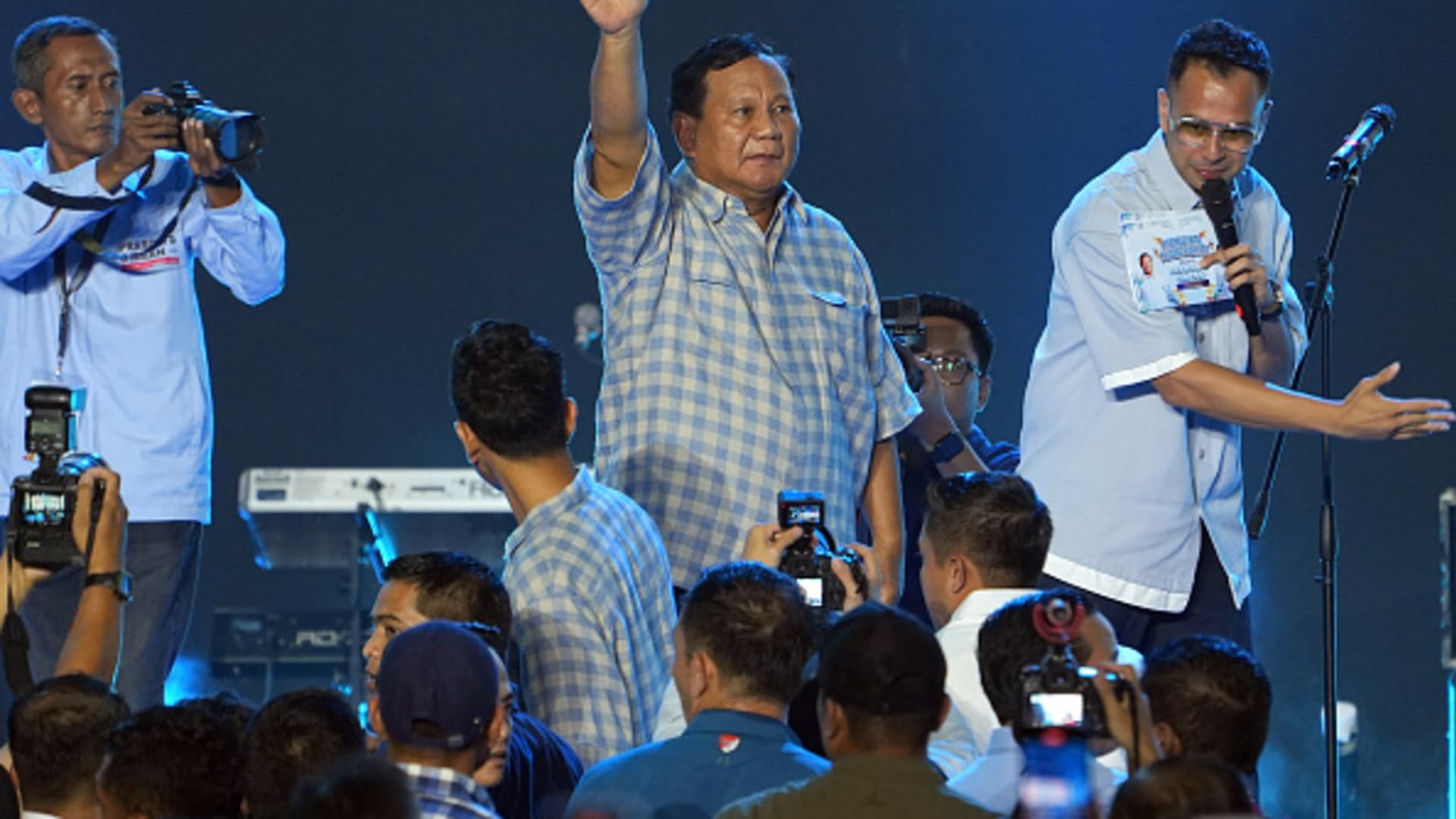

Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia’s presidential candidate and defense minister, center, waves to supporters in Jakarta, Indonesia, on Wednesday, Feb. 14, 2024. Prabowo declared victory in Wednesday’s presidential vote, citing independent pollsters, putting him on course to lead Southeast Asia’s largest economy after two failed attempts.Â

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

JAKARTA â Indonesia’s Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto is set to become the next president in October after voters handed him a strong mandate at the Feb. 14 election.

With about 75% of the votes counted, the latest tally from the General Elections Commission shows that Prabowo, together with his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka â the son of current president Joko Widodo, have garnered nearly 59% of the votes so far.

Prabowo, who’s been rebranded from a controversial ex-military general to a dancing grandpa, has pledged continuity with the current administration’s policies.

Investors and businesses alike will welcome the message of continuity â but some suggest Prabowo may have ideas of his own.

Under Widodo, Indonesia’s gross domestic product has grown steadily at around 5% over the past decade â barring the pandemic years of 2020 to 2021.

Foreign direct investment has risen to record highs, and much of it channeled into the booming nickel sector, while the government has spent lavishly on infrastructure.

“I think it’s just too risky for the next president if he changes everything with regards to economic policy,” said Josua Pardede, chief economist at Permata Bank in Indonesia. “Because at the end of the day, the voters will compare the economic policies which have been delivered well by the incumbent president with the next president.”

Others suggest Prabowo could in fact diverge from the current administration’s policies in key areas.

“People have assumed that this is very solid continuity, I think it’s more loose continuity with a risk of backward steps in some areas,” Peter Mumford, who leads Southeast Asia coverage for political risk consultancy Eurasia Group told CNBC. He flagged Prabowo’s high-spending plans as a particular cause for concern.

On the campaign trail, Prabowo’s discussions on economic policy were limited, and mainly focused on promises to continue the Widodo administration’s signature downstreaming policy.

That policy used export bans and tax incentives to attract businesses into processing nickel ore in Indonesia. The government is now trying to leverage this to build a domestic supply chain for electric vehicles, and roll out similar policies for other metals like bauxite and copper.

“It’s about time Indonesia becomes an industrial country, instead of a country that just produces raw materials,” said Erick Thorir, minister of state owned-enterprises, told CNBC’s Martin Soong in mid-February.

Thorir, a close ally of Prabowo who’s expected to play a key role in the next administration, suggested the presumptive president was keen to expand downstreaming into other areas as well â in particular, processing food and agricultural goods.

While campaigning, Prabowo touted ambitious programs to open up 4 million hectares of agricultural land and massively expand Indonesia’s use of biofuels, arguing it will contribute to the country’s national security.

Big promises, big price tags

Prabowo has also made a series of expensive promises, pledging to provide free school meals, increase village funds, and offer direct cash assistance for the poor.

It is estimated that the free school meals program alone could cost from about 400 trillion to 450 trillion Indonesian rupiah (about $25.6 billion to $28.9 billion), local media reported.

How this will be paid for remains murky. One Prabowo surrogate, campaign aide Eddy Soeparno, had initially suggested the administration may trim fuel subsidies â but he later walked back on those comments.

Prabowo has also talked about raising revenue through improving tax collection, proposing to establish a special revenue agency independent of the finance ministry.

However, some analysts were skeptical when asked about this, raising concerns this could complicate financial policy, weaken the finance ministry’s ability to impose fiscal discipline, and would not necessarily improve tax collection.

As such, some have warned that Indonesia might see an increase in deficit spending.

Prabowo’s economic team has reportedly suggested that fiscal rule limiting Indonesia’s budget deficit to 3% could be revised to 6%.

Reaction to a potential fiscal expansionism has been mixed. “I do personally think we think we have room to increase our credit ratio, we have room to increase our fiscal deficit slightly,” said Irwanti, chief investment officer of Schroders Indonesia.

Indonesia’s debt-to-GDP ratio stood at just 38.1% in September, according to CEIC Data â that’s lower than that of its neighbors like Thailand and Malaysia.

Irwanti argued that the key is making sure the money is spent “productively” if debt rises.

Mumford, however, is more skeptical. He cited Prabowo’s tendency toward “fiscal populism” and “questions around governance.”

Prabowo’s only experience in government office has been as defense minister under the current administration, he said.? In this position, he has overseen a sharp increase in defense spending sparking questions about his expensive purchase of second-hand jets and a murky food estates program.

Investors want clarity

For now, investors are hoping for more clarity when Prabowo announces his choice of finance minister.

It is widely assumed the current finance minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati, will not continue in her role under Prabowo’s new government given his coded attacks on her record, reportedly due to rows over the defense ministry budget.

For many investors, Sri Mulyani has had a near totemic importance. Rumors of her resignation in January caused a brief slide in the Indonesian rupiah.

However, financiers in Jakarta remain relatively sanguine about her likely departure anticipating that her successor will have suitable technocratic credentials.

Many names have been floated so far.

Among them is Indonesia’s Health Minister Budi Saidikin, widely seen as a capable minister, having helmed Indonesia’s pandemic response since assumed his position in 2020. He previously served as president director of Bank Mandiri before entering the ministry of SOEs. As deputy minister there, he oversaw the Indonesian government’s decision to take a controlling stake of the Grasberg mine, which holds one of the largest gold and copper reserves in the world.

Another name that has emerged is Suhasil Nazara, current deputy minister of finance. He could be a reassuring pick for some investors given his closeness to Sri Mulyani and reputation for financial orthodoxy, according to Permata Bank in Indonesia’s Pardede. With a background in academia and then civil service, his apolitical profile might let him sneak past candidates that come with backers but also critics.

A potential wild card pick suggested by some is Minister of Trade Zulkifli Hasan, a self-made businessman and head of the National Mandate Party. Such a pick could make markets nervous given his lack of a financial background â but his moves to build a close relationship with Prabowo might end up counting for more.

The list of potential candidates so far is long, and it’s unclear who will eventually get the job.

But one thing is clear: any final decision on the finance minister will be the result of months of negotiations with coalition partners, before Prabowo eventually takes power in October.